From THE LESS PEOPLE KNOW ABOUT US

FIVE

By the time the daffodils bloomed that year, some semblance of normalcy—or at least a new kind of normalcy—was starting to take shape. Though she was still shopping too much, Mom had taken on a few new clients, and Dad had thrown himself headfirst into the farm, accumulating animals and planting acres upon acres of hay. He spent the first half of his day at the grocery, where he was the produce department manager, and the second half on the farm. If his fourteen-hour workdays exhausted him, he never let on.

For her birthday that year, Mom requested a day-trip to Whitewater Memorial State Park, one of her favorite places in Indiana, and Hueston Woods, a park just across the border in Ohio that we had visited often as a family. This was an impromptu decision, and one I was thrilled about. I put on my gym shoes and hoped my parents would let me walk around the nature center at Hueston Woods again. There was a rabbit there that when I was a toddler I had decided was the Easter Bunny. I still liked to go see it.

We rarely took extended vacations—the farm made that nearly impossible—but these day-trips around the state were happy occa-sions. Mom and Dad were always more affectionate when we were driving around some lake or down a leafy country road. Often I would notice them holding hands in the front seat. My mother especially came alive as Portland faded in the rearview.

Just as I was about to bound out of my room, the yelling started. I sat back down on my bed and listened. I couldn’t believe Dad was acting like this on Mom’s birthday. Since Grandpa died, it seemed my parents’ rules of engagement had been upended. Occasional nervousness about money had turned into frequent and angry fights. Dad leveled an accusation that Mom was spending too much money and Mom wailed in objection. She needed more, she said, Dad didn’t know how expensive things were. I sat on my bed and thought about the ruby-studded lion in my jewelry box. I thought about all the wrappings I had shoved down deep in the trash can like Mom had instructed. I closed my door gently.

A few hours later—after a tentative truce was reached—we were driving the scenic loop through Whitewater. A few fisher-men in motor boats dotted the reservoir, and although the trees were still mostly bare, a verdant underbrush was beginning to transform the landscape into something more summery. From the backseat I could feel the tension between my parents as we sat in an icy silence. Mom’s gaze was fixed beyond the guardrail and Dad gripped the wheel with both hands. When we got to Hueston Woods, I didn’t ask to stop at the nature center. The only time we got out of the truck was to get gas. The few words my parents spoke pertained to directions.

The sun had set by the time we got back to the farm. Mom planted herself in front of the TV and Dad went out back to work on evening chores. I followed him into the barn. Before he even turned to acknowledge me, I blurted it out.

“She buys a lot of jewelry from the TV, Dad. And she shows it off. She told me not to tell you.” The admission erupted from within me like a broken fire hydrant. My dad put his hands against the rough wall of the barn and exhaled in anger.

“And she makes me get it from the mailbox,” I blurted.

My father snapped his head toward me and set his jaw hard. He was adamant I never cross the highway alone, and I under-stood why. It was busy. Sometimes our barn cats tried to follow me and I was afraid they would get hit by a car.

“You’ve been crossing the highway by yourself.” He said it like a statement, not a question.

Part of me wished I could take it back. But a bigger part of me hoped that with the truth out in the open, my parents could resolve their ongoing arguments about money.

I was still visiting the animals in the barn when Dad confronted Mom about what I had said. Whether it was a noisy crescendo or subdued surrender, I don’t know. But soon after, the flow of cheap, chunky jewelry suddenly stopped for good.

It was during a previous trip to Hueston Woods that Dad had discovered a passion. I was still squirming in my car seat as he and Mom drove into the park. Posted near the entrance, my dad noticed a sign that said Donkey Show above a crooked arrow. His interest was piqued.

There are pictures from that afternoon. Whenever Mom got them out she loved to recount how curious my father was made by that sign. “What in the world could that be,” he’d said. How he had driven the curving state park roads with his body hunched forward in his seat. When she got to the pictures of my father holding me, my arm reaching out to timidly pat one of the sturdy creatures, she remembers Dad saying, “I’m going to have one of these someday.”

Ten years later, Dad and I were exploring the fall swap meet—an annual event where farmers sold and bought every-thing from old tractor parts to fuzzy baby chicks—at the Jay County Fairgrounds when we came upon a miniature donkey, docile in his small pen behind a handwritten sign that said $300. The donkey came home with us; his name was Odie.

While the rest of the farm resembled a modern-day Noah’s Ark—a couple of llamas here, a duo of Bronze turkeys there— my father’s commitment to raising donkeys endured, transitioning from miniature donkeys to mammoth donkeys. At the peak of his hobby farming, my dad had forty-seven donkeys. Donkeys, of course, have historically been used to carry heavy loads and protect sheep. My father’s donkeys were for show and for trail riding.

A couple of weeks after Mom’s birthday, I came in the back door and found my father in the kitchen, leaning against the counter with the receiver wedged between his shoulder and his head. He was studying the orange carpet with a furrowed brow. I took my time investigating the refrigerator.

“I’m not sure why I’m paying you if you’re not going to send me anything,” he said. I could hear his hand smack the counter with indignation. There was silence then, while some-one somewhere explained something. So Dad wouldn’t think I was eavesdropping, or get mad at me for leaving the fridge open too long, I returned to the backyard and my book.

At the table that night, where I was the only one eating some leftovers I had reheated myself, the mystery was revealed. My father’s The Brayer magazine had not been arriving.

“Pam, I called them already,” my father explained. “They said they have absolutely been sent, and that it must be a problem on our end.”

I moved the corn and squash around with my fork and thought about the last issue of the magazine I had seen on the end table. I guessed it had been a while. The magazines were more like monographs, each one thick and heavy like the JCPenney catalog. Sometimes when I was bored, I would attempt to read one of the articles—something about rescuing wild donkeys or breaking them for trail riding—but rarely made it through the first page before my curiosity waned.

My mother took a sip of her Diet Rite. “I think you should just cancel it,” she said.

When the phone bills started disappearing, my mother showed more concern.

“It’s definitely Willy,” she announced one evening while we were watching TV in the living room. Dad was in his farm clothes, getting ready to go outside and feed the animals, and I was avoiding homework by lying on the carpet in front of the TV.

“That’s a stretch, Pam,” Dad said, incredulous.

“Think about it. Willy’s son works at the phone company. I bet he’s going down to the billing department and snatching ours out of the bunch.”

My dad stood up, about to make his way to the barn. I flipped over on my elbows to see his reaction.

“Okay. If it’s Willy, why is he taking my Brayer and Mules and More? That doesn’t make a whole lot of sense.”

“Yeah—and my pen pal letters, Mom? Why would anyone take those?” I interjected. No one seemed bothered that my friends’ letters weren’t arriving. As a twelve-year-old farm kid, those notes were my social lifeline. Since Greg and Kathy had sold the skating rink, I never saw Carrie anymore. She went to school in a different district and so we had taken to correspond-ing by mail. My Amish friend Katie also sent me letters during the summer.

My mother looked at me but I could tell my pen pal letters weren’t high on her priority list.

“Obviously when we’re all gone during the day, Willy, or someone over there, must be taking the mail.” Mom stated her opinion as fact, as she always did.

My dad sighed and shook his head. “I’m going out to the barn. If you really think it’s Willy, I’ll go over there again,” he said before disappearing into the dark kitchen and out the back door.

Willy lived on the parcel of land behind the farm. His place was so far back from the road, though, I had only ever seen him from a distance. I thought he was gaunt and mean-looking and felt his wife wore a permanent scowl.

Grandpa Elliott and Willy had waged a years-long war over two feet of land that Willy had thought was his. The land belonged to Grandpa—a surveyor came out to confirm that—but Grandpa said that Willy had at times moved segments of the fence line in the middle of the night. A few years before Grandpa died, Dad got fed up. With his rifle on the passenger seat, he kicked up plumes of dust as he sped down the gravel road to Willy’s. Mom stationed herself in their bedroom, at the back of the mobile home, with the phone in her lap, listening hard for gunshots and ready to call the sheriff when she heard them. I sat next to her, my heartbeat loud in my ears.

We hadn’t had trouble with Willy since then, but now Mom’s theory made sense. Our yellow metal mailbox stood unattended all day; Willy would have ample time to take what he wanted. It didn’t seem likely he would steal our letters and magazines, but maybe he was just that mad about the property dispute.

Mom didn’t send Dad over to Willy’s. Instead, she got us a PO Box in Portland. She checked it every day on her way to or from a client’s. Magazines, bills, and letters from Carrie and Katie still went missing.

One night, while Dad cut up vegetables from the garden, I listened from the living room as Mom explained that there were probably people working in the post office who were stealing our mail. Dad, skeptical, asked why anyone would do that.

“People steal your mail to get your social security number or your account information,” she said with unearned authority. She had seen something on the news about something similar happening in the Muncie post office. I didn’t hear Dad ask any more questions, just the rhythmic sound of his butcher’s knife on the cutting board. A few days later, our phone was shut off.

“What am I supposed to do if something happens while I’m home alone? What if there’s a fire?” Mom and I were making our monthly pilgrimage to the mall. I was trying to make the case that it wasn’t safe for me to be home alone in the summer, without a working phone.

“Get the animals out, get yourself out, and let the place burn,” she said dryly, not taking her eyes from the road.

I knew Mom was frustrated. She said she had spent hour that week at the post office and police department begging for formal investigations to be launched. In the meantime, she had secured another PO Box in Albany, two towns over, in an attempt to stay in front of whoever was stealing our mail. At some point, Mom had begun calling what was happening to us identity theft.

Dad stayed out of Mom’s way while she handled the crisis, diverting his attention to the farm. In high summer he was always buried in chores, sometimes taking a day off from the grocery just to bale hay. His equipment purchases hadn’t quite kept pace with his ambition; the model 750 John Deere he had bought new in 1985 was woefully inadequate to handle the forty acres of hay he had planted in three years’ time.

“Who do they think it is?” I reticently asked.

“They don’t know, honey,” she said, looking over her shoulder to merge onto I-70. “Probably somebody who doesn’t like us.”

The hair on my arms tingled. Who didn’t like us? I couldn’t think of one mean thing we’d done to anyone. What was it about us? Why were we good targets?

Several weeks later there was a break in the case. Mom came home with a cardboard box full of magazines and bills. She said the police had found it in an alley behind someone’s house in Portland. Relieved, I excitedly pulled my pen pal letters from the pile atop the kitchen table. I was on my way to my room when I heard Dad raise his voice.

“Pam, this has gone too far. I’m going down there tomorrow to talk to them myself.”

“You can’t do that because you didn’t file the police report—I did—so they can’t talk to you about it,” my mother said in exasperation.

I quietly shut my bedroom door. It didn’t bother me that Mom and Dad were fighting; this whole thing would be taken care of soon, I thought.

I look back with a lot of pity on my twelve-year-old self. If only she knew how bad it was about to get.

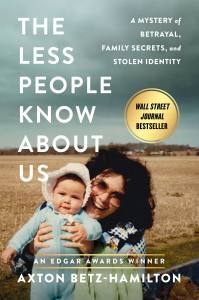

In this powerful true crime memoir, an award-winning identity theft expert tells the shocking story of the duplicity and betrayal that inspired her career and nearly destroyed her family.

Axton Betz-Hamilton grew up in small-town Indiana in the early '90s. When she was 11 years old, her parents both had their identities stolen. Their credit ratings were ruined, and they were constantly fighting over money. This was before the age of the Internet, when identity theft became more commonplace, so authorities and banks were clueless and reluctant to help Axton's parents.

As a result, Axton spent her formative years crippled by anxiety, quarantined behind the closed curtains in her childhood home. She began starving herself at a young age in an effort to blend in--her appearance could be nothing short of perfect or she would be scolded by her mother, who had become paranoid and consumed by how others perceived the family.